11.01.2018 - 15:34

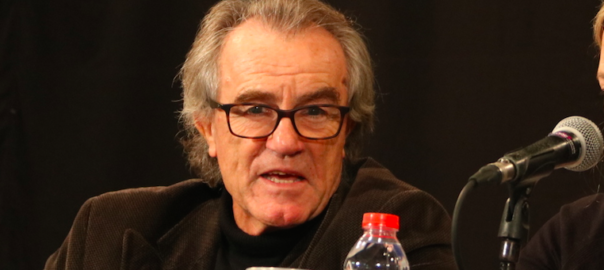

“I don’t know how we’ll get out of this one” says top Spanish jurist Javier Pérez Royo, a Professor of Constitutional Law in Seville who has come out in support of a referendum in Catalonia and has denounced Madrid’s crackdown. In this interview he admits to being pessimistic about the future of Spanish democracy owing to the decisions taken by the Spanish government with the support of the PSOE. Pérez Royo claims that “the legal action [against pro-independence leaders]” together with the charges pressed by the Spanish Supreme Court —which he calls foolish— “leave no room for a political solution based on a ballot”. Pérez Royo laments that “it’s a bleak outlook; it’s nearly impossible to stop the Supreme Court” and adds that we find ourselves in the middle of a state operation that aims to use this opportunity “to emasculate Catalan nationalism”, to say to them: “You won’t get to do this ever again”.

—Were you surprised by the Supreme Court’s interlocutory statement about Junqueras?

—I wasn’t. It is consistent with every decision taken thus far, first by Madrid’s Audiencia Nacional and later by the Supreme Court. It’s entirely consistent, albeit with minor discrepancies concerning the cautionary measures adopted. The central issue is that it characterises the conduct [of the defendants] as a crime of rebellion. So far, the main focus has been on the cautionary measures and their imprisonment pending trial, but the crux of the matter, the key element, is that rebellion charges have been pressed and, if the investigation is pursued on that premise and they go to trial, it will be awful. Awful, because the penalties are extremely serious. On this point there is a rather general agreement between the Audiencia Nacional and the Supreme Court. They see eye to eye, now. And I’m not sure whether things will be seen in a different light as the investigation moves along.

—What do you think about the arguments they are using to hold the Catalan prisoners on remand?

—They make no sense. The Supreme Court’s interlocutory statement makes a fair description of the process and its unlawful nature. The Catalan government and the parliamentary board acted in an unlawful manner, indeed. In the same vein, the Constitutional Court banned the [independence] vote and they disobeyed its instructions. The problem lies with the legal characterisation of these actions which cannot be construed as a crime of rebellion even though they’re unlawful —the defendants openly admit that they reject the Spanish constitution—. In contrast, the public prosecutor’s office, the Audiencia Nacional and the Supreme Court claim otherwise. That makes no sense.

—It is surprising to read that the Spanish Supreme Court holds the victims of the Guardia Civil violence responsible for the crackdown.

—Yes. Spain’s deputy PM instructed the Spanish police to charge and that is presented as evidence of the Catalan vice president’s culpability. One person is being held to account for someone else’s orders. So, they claim that a crime of rebellion has been committed because of the violence caused by the Spanish police and Guardia Civil charges against members of the public who wanted to vote on October 1. If they hadn’t called the vote, there would have been no violence. That’s utter nonsense. And that is why they had to drop the European Arrest Warrant [on the Catalan leaders who fled to Brussels]: with that argument they would have split their sides laughing, in Belgium.

—Can that attitude by curbed in any way?

—Sure, but not for a long time.

—Once the issue can be taken up to an international court?

—Yes. But first the case must run its course and be tried in Spain’s Supreme Court. That will mean a change from the current phase, in which the investigating magistrate can do whatever they fancy and the court merely issues interlocutory statements in preparation for the trial. Eventually the Supreme Court will have to consider the case carefully because the defendants will have a right to appeal on the grounds of unconstitutionality and, eventually, to lodge an appeal with the European Court of Human Rights.

—Junqueras’ lawyer said that last Friday’s interlocutory statement reads almost like a ruling.

—It is a preview of the ruling: “there’s been a crime of rebellion …” and so on and so forth. I cannot prove it, but I get the impression that the matter must have been discussed in a plenary session of the Supreme Court, where the president of the Court must have spoken to all the judges that make up Court number 2 and clearly they must have agreed that that’s the path they have to go down.

—Is it a joint state operation by the prosecutor, the Spanish government and courts of law?

—Absolutely. They have activated the sterilisation of Catalan secessionism. An operation of emasculation. They want to make the most of this opportunity to do just that, to sterilise, to say “You won’t get to do this ever again”. They want to prevent Catalan nationalism from ever doing this again.

—Could that have consequences?

—Of course. But they have tried that sort of thing before and failed.

—You said that “this won’t end well” …

—Yes, when a court of law argues a case the way the Supreme Court is doing … We had violence because the Spanish deputy PM ordered baton charges, but we are holding the Catalan government to account? And so you claim they committed a crime of rebellion? When the Supreme Court resorts to that sort of reasoning, what can you expect?

—What do you expect will happen?

—I don’t know. But it’s looking pretty bleak, among other reasons because stopping the Supreme Court is nearly impossible now. And the entire Catalan political process will remain bogged down until the Supreme Court stops. Nineteen members of parliament are facing charges at the moment, and there could be more in the coming weeks. And additional cautionary measures might be adopted against those who have been charged but have not made a statement in court yet. How can you possibly form a government that way? How long will cabinet members remain under threat? Nineteen of them will likely go to court at the end of this year —if there are no delays— and they will almost certainly be banned from holding office. Many will likely receive long prison sentences. So what happens with the current parliamentary term?

—All that conflicts with the legitimacy that the electorate has given the political leaders who have won the elections.

—Yes, indeed. They called an election to find out what choices the people would make and see if they could put things back together. But they started filing criminal charges and destroyed everything. Any chance of a political solution via a ballot has vanished with the prosecutions.

—Perhaps some intellectuals and political leaders on the left have not shown their solidarity, but people like yourself and other jurists have denounced the situation.

—Well, at the moment the state’s reaction is brutal. It is so, among other things, because I get the impression they’ve found out that there is a social base that demands that sort of reaction, that is receptive to those policies. Will that be short-lived? We don’t know. It might demolish the whole edifice of regional devolution in Spain. Either the Catalan issue is resolved or Spain won’t have a democratic government. I don’t know how we’ll get out of this one. The Catalan problem is Spain’s problem. Either it is resolved democratically in a way that is acceptable to Catalonia and Spain or we won’t have a democracy in Spain as a whole. We’ll see.