16.01.2025 - 03:14

|

Actualització: 16.01.2025 - 03:15

Abozeb Hamoud Ramadan lives in one of the poorest neighborhoods of Qamishli, in a mud house. We see him sitting under an old blanket, alone, head bowed, unable to lift his head. His body is here, but his mind is far from the warmth of this room. He doesn’t speak unless we ask him questions. He is pale and very thin. He’s only thirty-one years old but looks much older. He gazes at the door and the light coming through the window, looks at the sky with tears in his eyes. He walks very slowly, unable to put his full feet on the ground, walking only on his toes. He vividly recalls where his body was burned, how they pulled out his teeth with electric pliers, and every drop of acid spray that burned his skin. Sometimes, we cannot believe what people tell us unless we see it with our own eyes.

Ramadan is one of the thousands of prisoners of the notorious Sednaya prison under Syria’s former regime. He was imprisoned from 2018 until the regime collapsed on December 8, 2024, after serving five years of mandatory military service in the city of Daraa (the epicenter of Syria’s 2011 uprising). In 2017, he had begun working in the capital, Damascus, but one night, while returning home, he was detained at a checkpoint.

I never imagined that a human being could be so monstrous and savage toward another. When I saw videos and photos of Sednaya prison after the regime fell, I thought they were exaggerated. I cannot fathom how these people endured so many years in that hell. The words I’ve transcribed do not capture the full catastrophe and suffering I’ve witnessed and felt. Writing this is difficult, and reading it will be, too. But it must be done.

—How were you detained, and why?

—The police called my name. They told me I was being summoned for reserve military service. I served for about three months, but then I fled. That’s when they arrested me.

—Where did you go after fleeing military service?

—I hid in an abandoned house in a suburb of Damascus for three days. I was still wearing my military uniform. I ate scraps from the trash. One night, they caught me and took me to the prison of the Palestine Branch (notorious in Syria for its torture methods). I spent a month there before they sent me to Sednaya’s hell.

—What was the prison like?

—Ten of us shared a tiny cell. There wasn’t space to lie down or stand up. We slept sitting. We used the same bucket for urinating and eating. The conditions were harsh. Sometimes we slept on corpses. I was detained there for six years. I never went outside, not even once. I didn’t see the sun during all those years. For seven months, I showered only once, with cold water.

—What food were you given?

—Half a piece of dry bread in the morning; half a boiled potato and a spoonful of wheat at noon; and another piece of dry bread in the evening.

—What torture methods did they use?

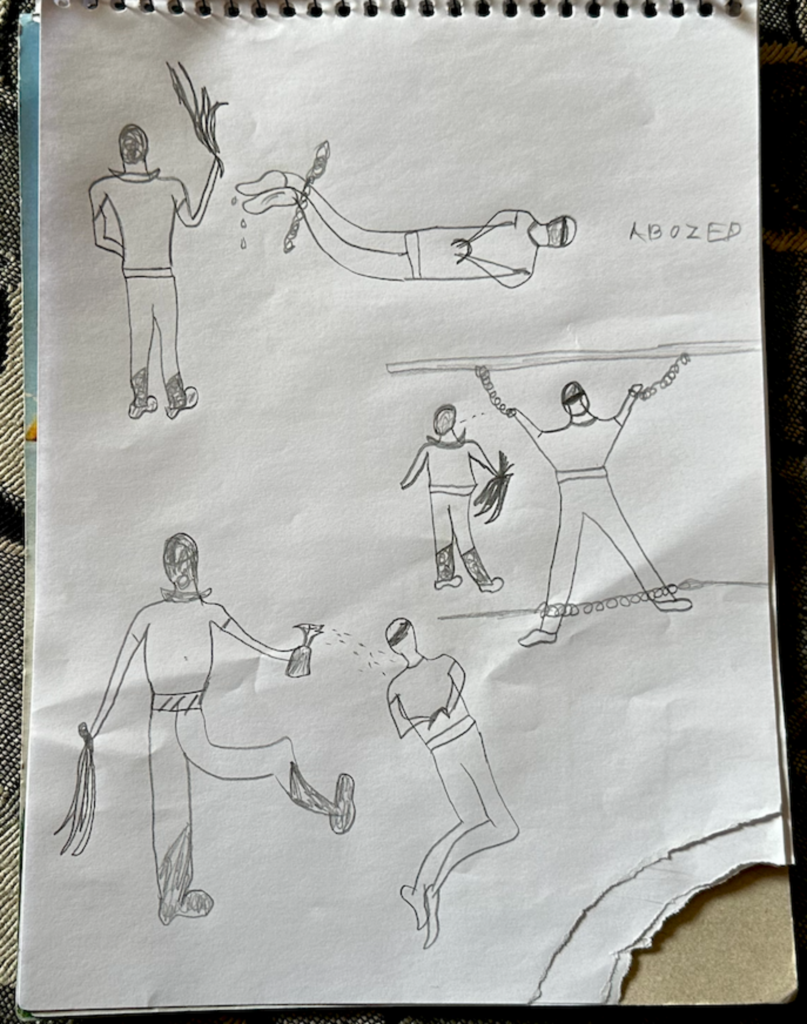

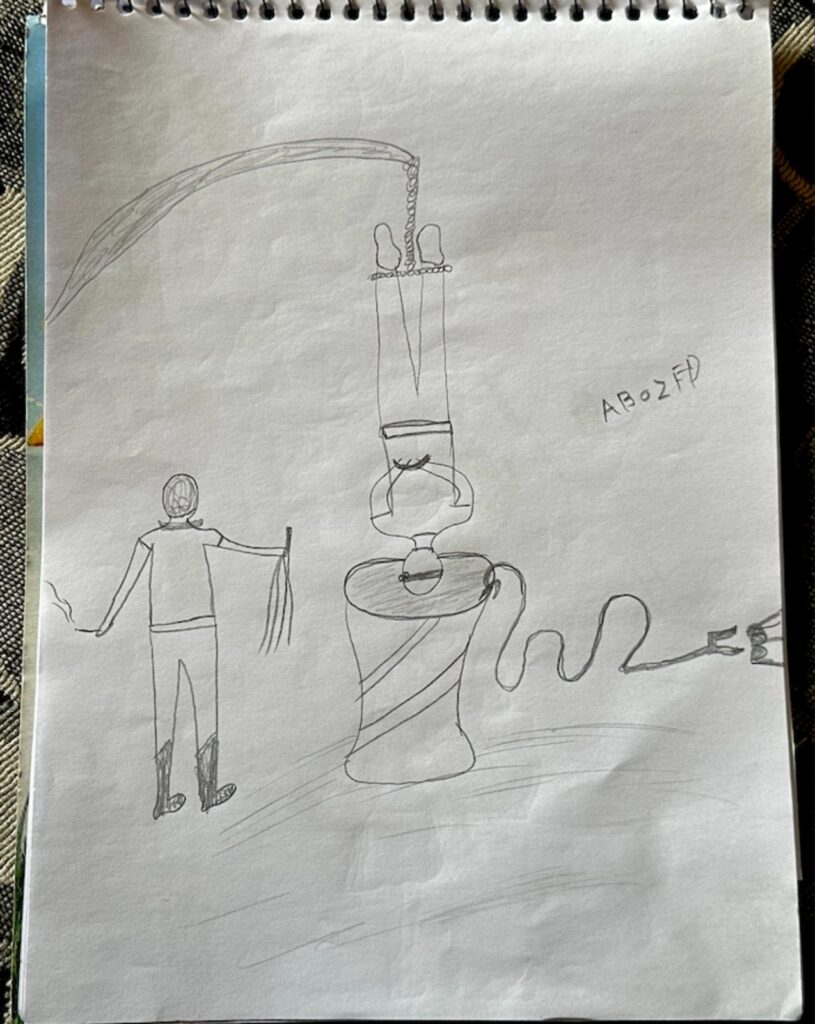

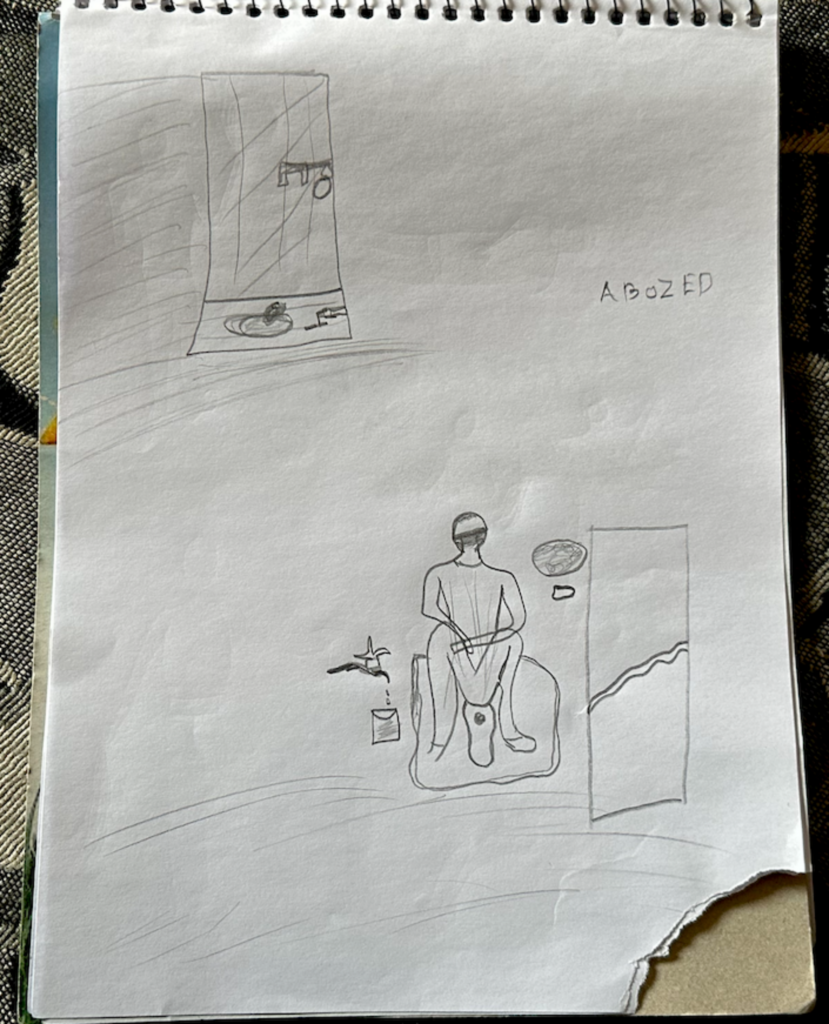

—They made us sit on a half-wooden, half-metal chair to electrocute us. They sprayed us with acid to burn us. They used barrels of acid to dispose of corpses. They pulled out teeth and nails with electric pliers. They beat us all over, especially on the knees. We were not allowed to lift our heads or look at their faces; we only saw their military boots. They burned women with acid after stripping them. They executed people and brought us the corpses. We were forced to sleep on the dead. We had only one blanket: we would lie on half and cover ourselves with the other half.

—…

—And there was psychological torture, too.

—Were you tortured?

—Yes, severely. When you enter Sednaya, you’re welcomed with 200 baton blows to your feet. That’s their greeting. If you lift your head, you get 250 blows. If you eat someone else’s food, it’s 500 blows. The worst torture I endured was when they burned my tongue with cigarettes and coals from water pipes [hookahs] for speaking Kurdish.

—What? They burned your tongue?

—I didn’t know there were surveillance cameras in the cell; they could also hear us. I asked something from my Kurdish cellmate, and they overheard me. They came and took me away. They beat me. They burned my body and my tongue.

—What happened when the regime fell?

—Two days before the regime fell, they came to our cell and called out two numbers. In Sednaya, we didn’t have names, only numbers. I was number 125. They announced that number 105 and another would be saying their goodbyes to the world in two days—they would be executed. They usually gave us food through a small hatch under the door. They only opened the entire door when they were taking someone to their death. When they opened the door after the regime’s fall, we thought they were coming to execute us. The door was wide open. They told us that the dog Bashar had fled and that we were free.

—What did you do?

—We walked out into the prison yard, crying and shouting. Some of us couldn’t walk because our feet had been beaten days earlier. Some of us stood still for half an hour, unable to believe it. We thought it was a joke or that someone important had come to inspect the cells. Then a man approached and asked why we weren’t moving. People took us to the city, gave us clothes and food. Those who didn’t know where to go were taken to a hospital.

—How did you contact your family?

—I was lucky I didn’t lose my memory [cries]. I remembered my name. I didn’t know my family’s phone number. I spent one night in a park. Then a family helped me. They recorded a video and posted it on Facebook. A friend of my brother, who lives in Germany, recognized me. He called my brother and told him I had been released. I took a bus to al-Hasakah, and then a family brought me here. My brother said he wouldn’t have recognized me if he had seen me on the street.

—How do you feel now?

—I still can’t believe I’m out, that I’m free. I think one day I’ll wake up and realize this freedom was just a dream. I still can’t put my feet on the ground because they were beaten so badly over the years. I was beaten 250 times for eating half a piece of bread from my cellmate. In prison, we would pretend to cook lavish meals and smoke as part of our gestures. Now I don’t even feel like eating or smoking.

—Are you receiving treatment?

—No. First, I need dental reconstruction. They broke and pulled out my teeth in prison.

—Did you paint this?

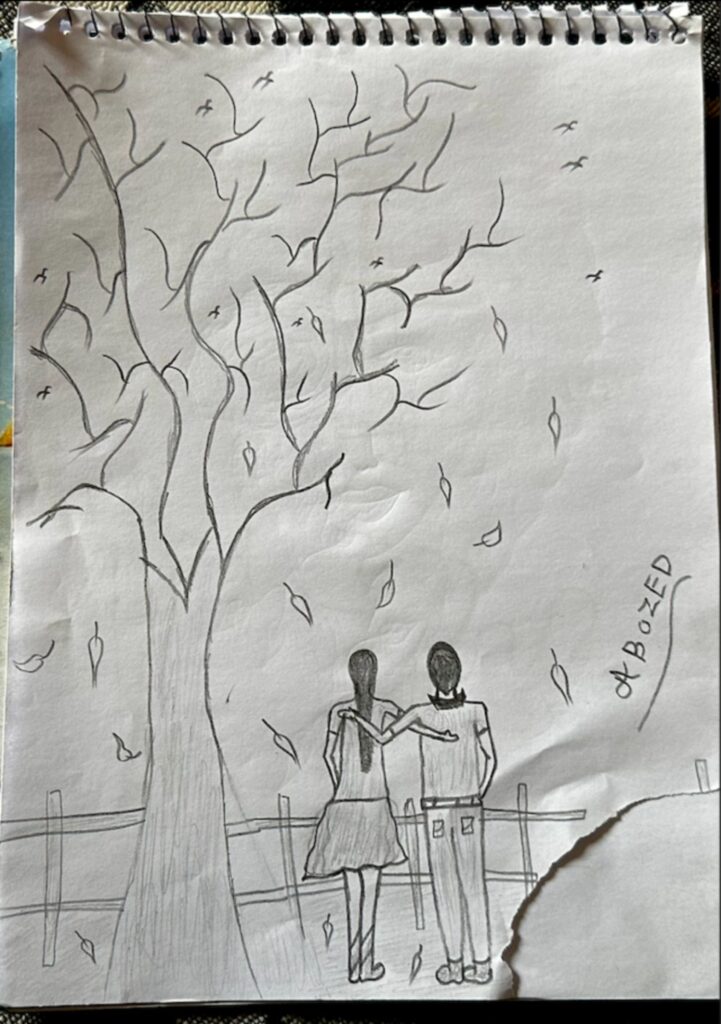

—I painted this. It’s the girl I loved but never married. She was Christian, and I am Muslim, so our families didn’t allow it. I don’t know anything about her now. The other paintings depict how they tortured us.

—Do you go out in the sun?

—I can’t stand sunlight for more than ten minutes. It gives me headaches.

—What are you thinking about now?

—That they’ll open the door and take me to my death. I remember the moment they opened the door for the last time when I thought it was my turn to die. Instead, they told us we were free.

—What do you want to do in the future?

—I want to leave the country. I don’t want to stay in this corner of the world. I’d rather be on another planet than here. If I stay here, I won’t improve. One day, I’ll wake up and realize this was all a dream and that I’m still in Sednaya.